If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row] This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

What the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) state

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

When reservations are superimposed on existing slums, they fail to acknowledge their existence. When coupled with the multiple planning authorities that plan for these areas, they point to an unknown future and in many cases, potential evictions.

What the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) state

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

When reservations are superimposed on existing slums, they fail to acknowledge their existence. When coupled with the multiple planning authorities that plan for these areas, they point to an unknown future and in many cases, potential evictions.

What the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) state

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

When reservations are superimposed on existing slums, they fail to acknowledge their existence. When coupled with the multiple planning authorities that plan for these areas, they point to an unknown future and in many cases, potential evictions.

What the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) state

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

An analysis of Proposed Land Use reservations on areas occupied by slums reflects the invisibilisation of slums — 48.7% area of slums are reserved as residential, 13.8% area of slums are reserved as forest, 13% area of slums are reserved as PlayGround and Recreation, 10.3% area is reserved as proposed roads. Further details are in Table 1. The ‘Slum Improvement Zone’, has not been included as a land use category in the proposed land use maps. The broad residential reservation in the proposed land use maps does not delineate this as a sub category.

When reservations are superimposed on existing slums, they fail to acknowledge their existence. When coupled with the multiple planning authorities that plan for these areas, they point to an unknown future and in many cases, potential evictions.

What the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) state

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

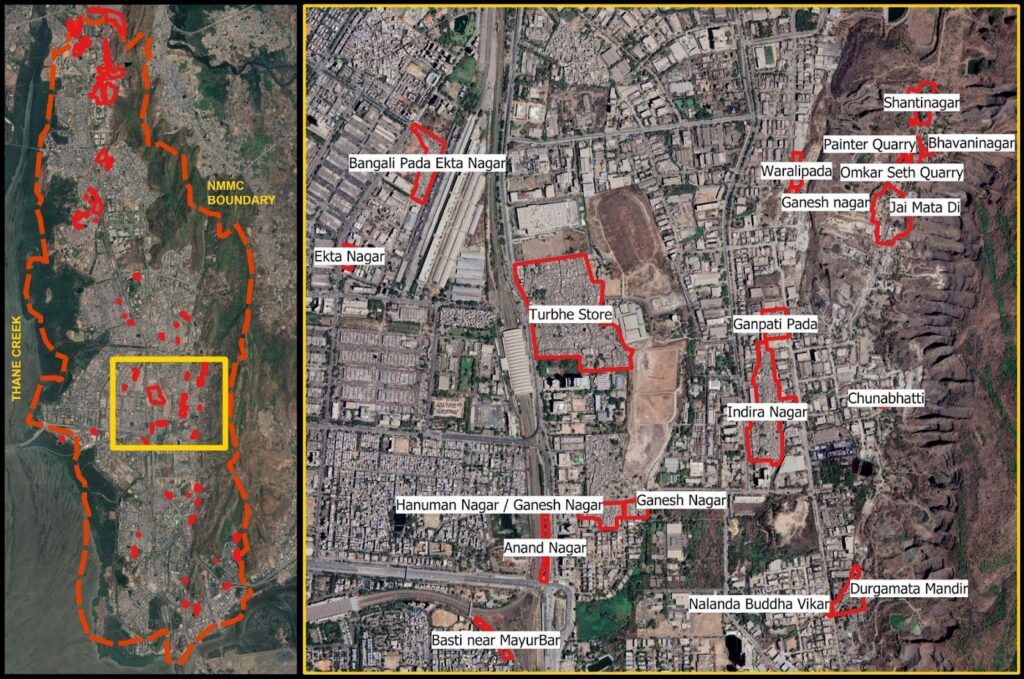

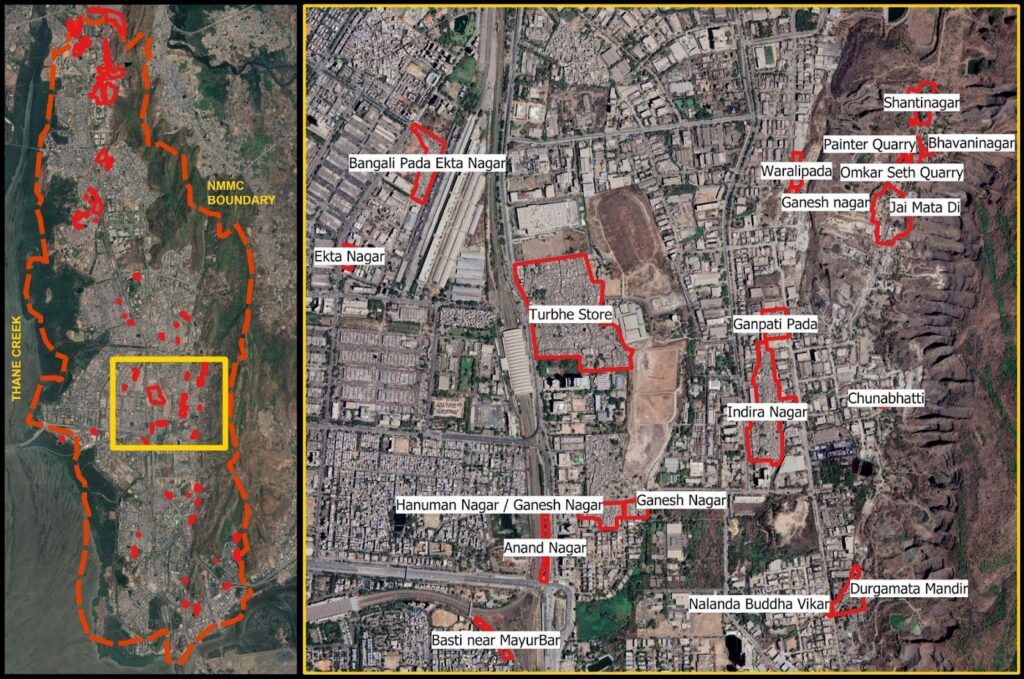

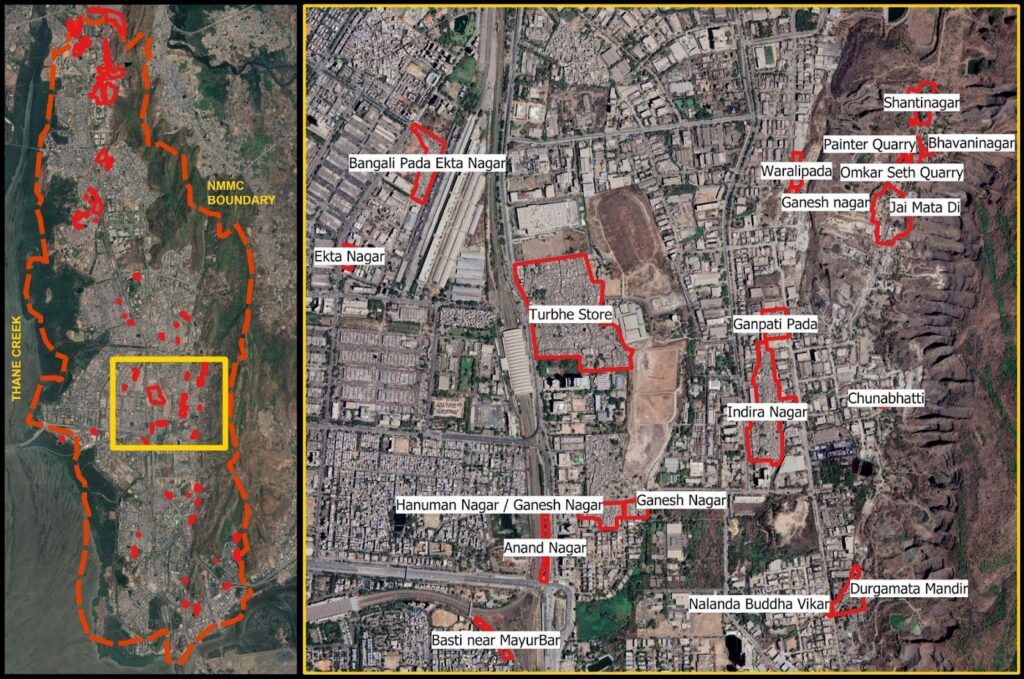

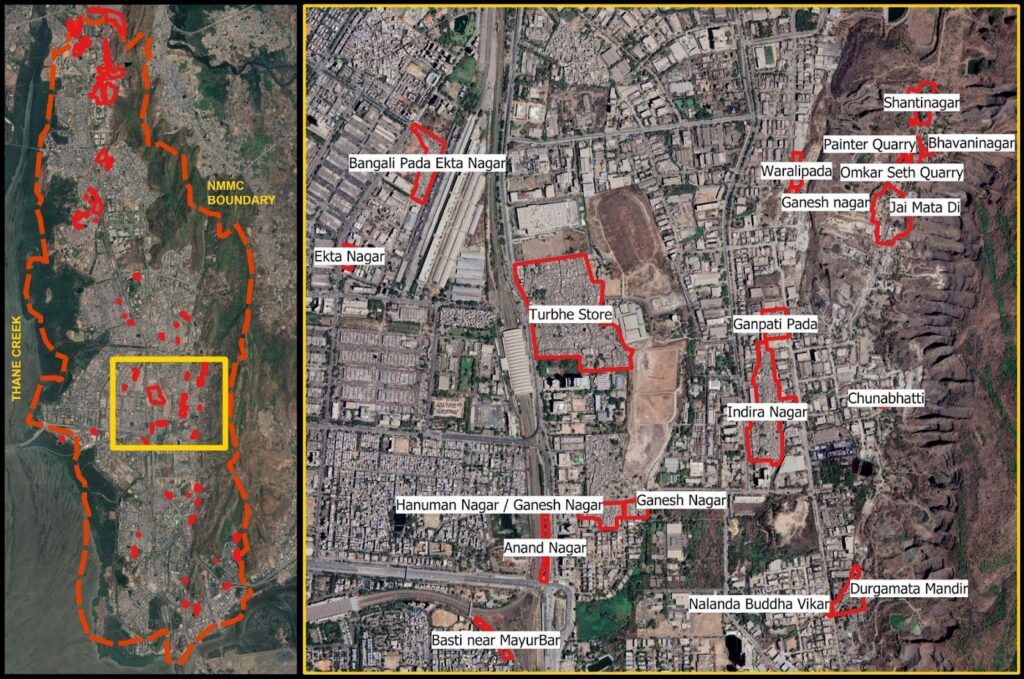

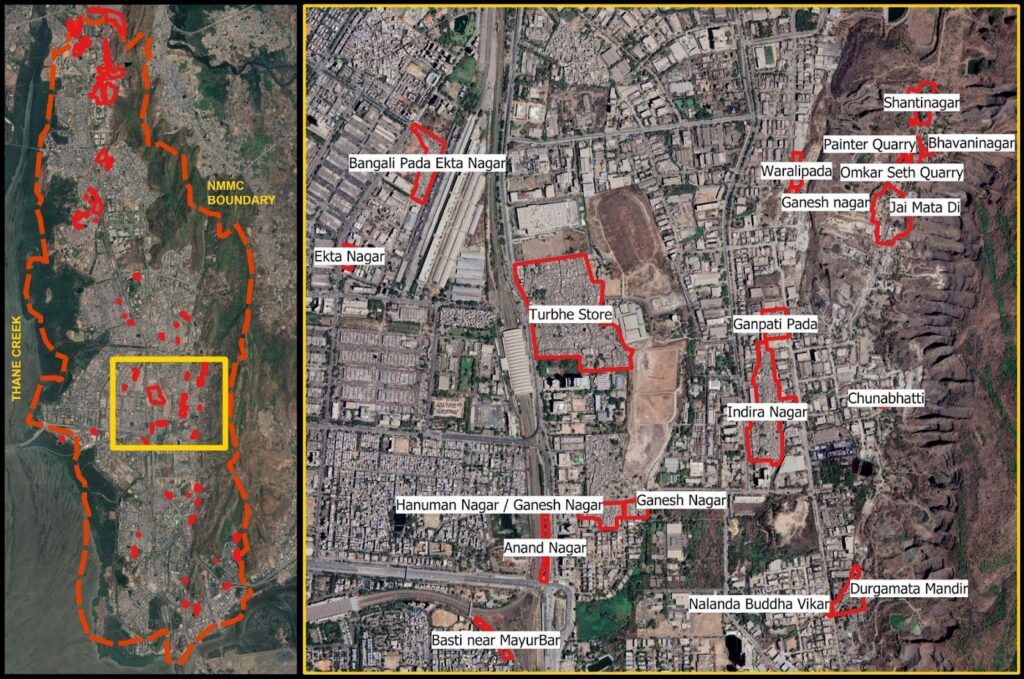

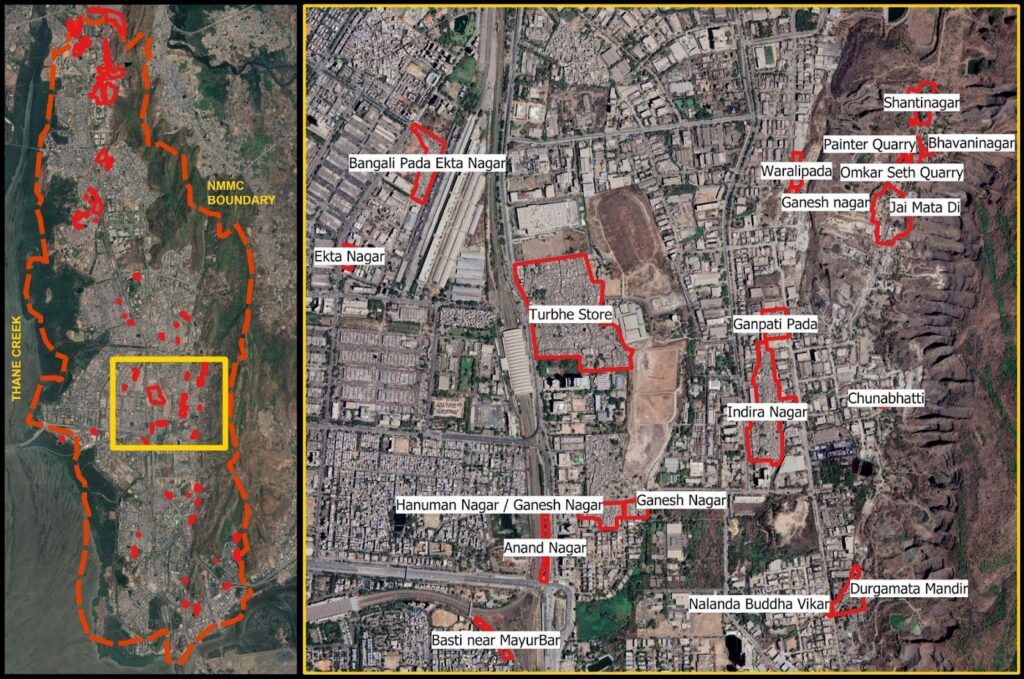

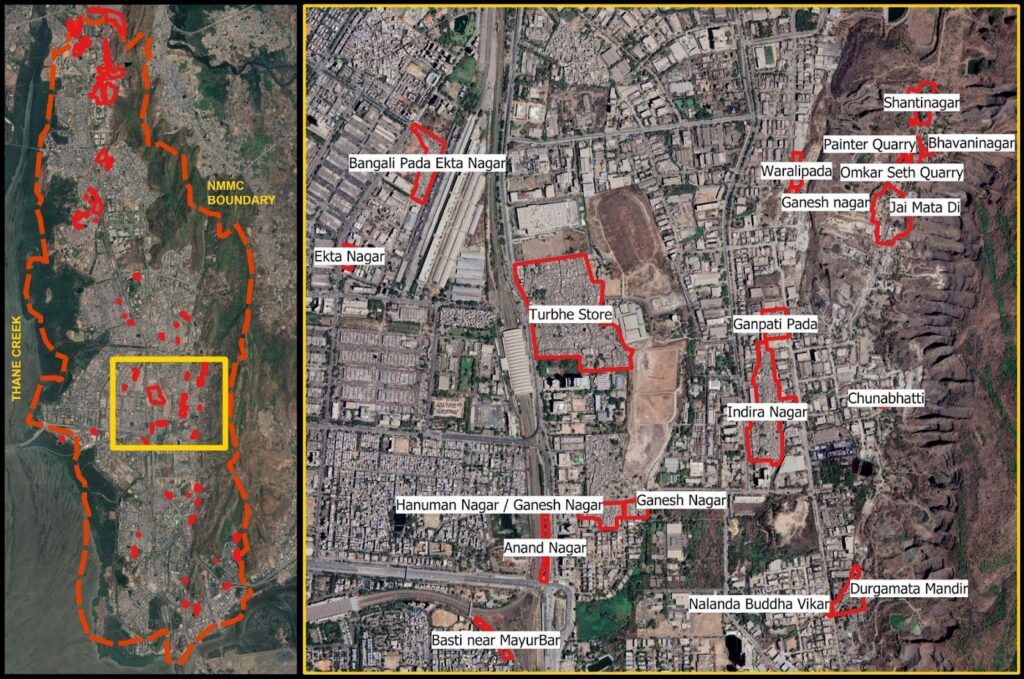

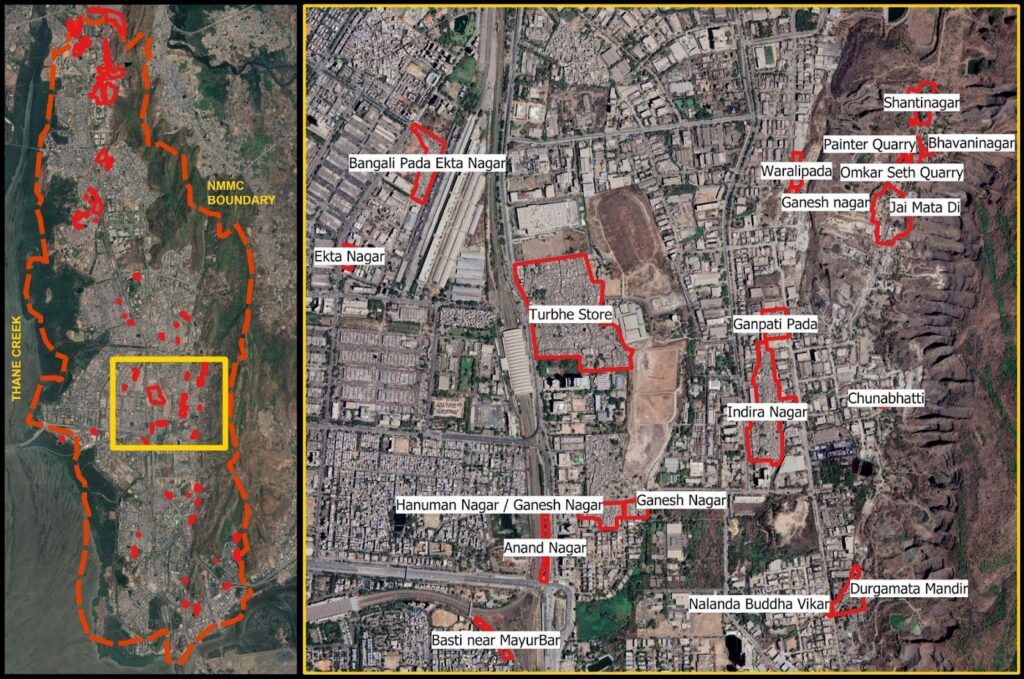

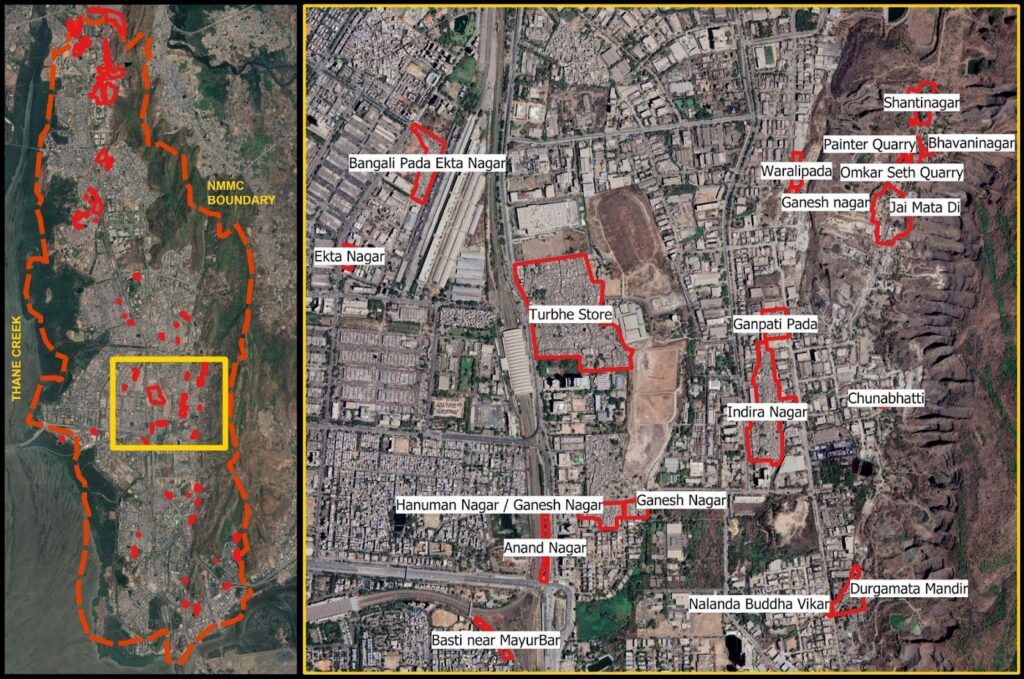

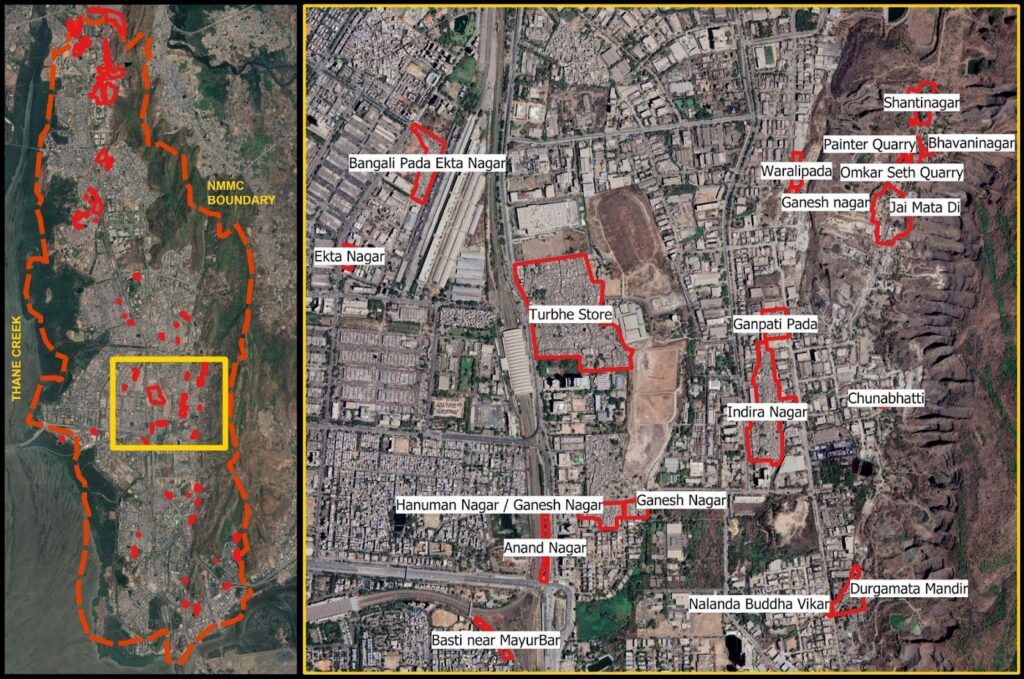

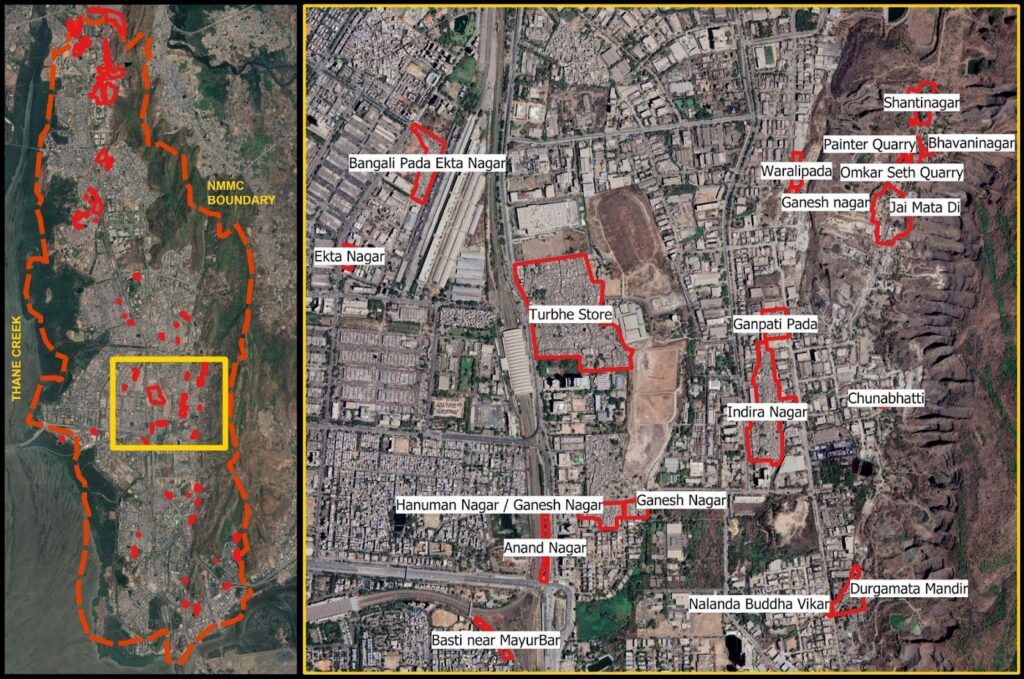

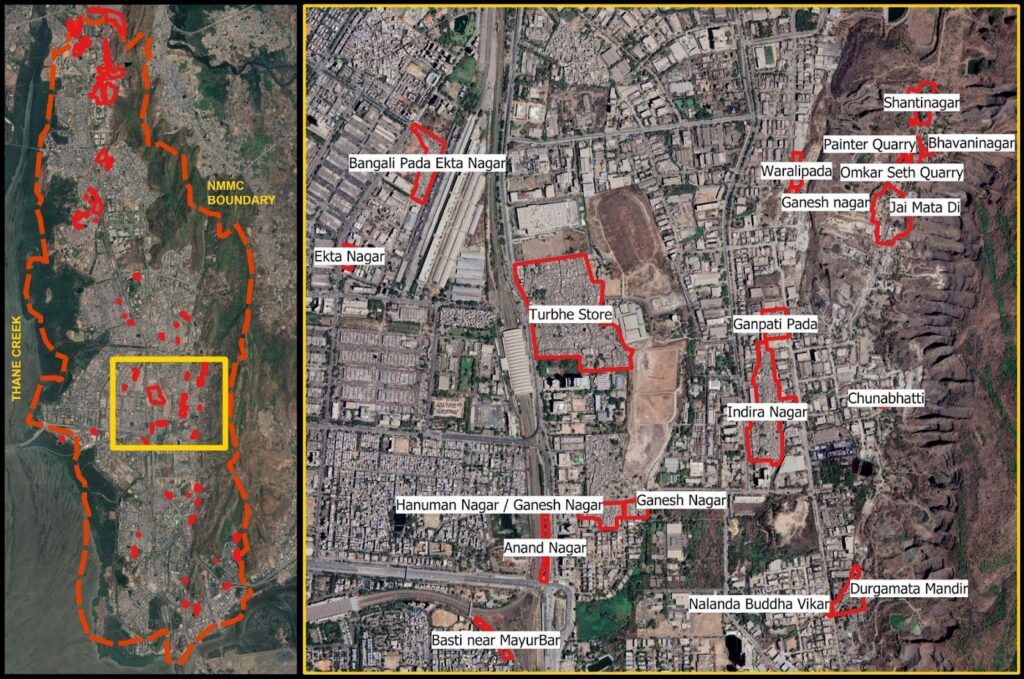

While the report has relied on the 2011 Census list that lists 47 slums within Navi Mumbai; of the 47 only 11 slums (23%) are within the jurisdiction of the NMMC planning boundary. Of bigger concern is that only 4 slums in the Vashi-Turbhe area (Turbhe Stores, Indira Nagar (part), Ganpati Pada, Warli Pada, Hanuman Nagar) are on land belonging to the state government. 36 slums are on land belonging to MIDC and CIDCO. Of the 76 slums identified in the 2022 YUVA-GHSS survey, only 28 lie in the NMMC planning area. Given that MIDC and CIDCO are Special Planning Authorities, the future of the majority of slums in the city remains in limbo.

An analysis of Proposed Land Use reservations on areas occupied by slums reflects the invisibilisation of slums — 48.7% area of slums are reserved as residential, 13.8% area of slums are reserved as forest, 13% area of slums are reserved as PlayGround and Recreation, 10.3% area is reserved as proposed roads. Further details are in Table 1. The ‘Slum Improvement Zone’, has not been included as a land use category in the proposed land use maps. The broad residential reservation in the proposed land use maps does not delineate this as a sub category.

When reservations are superimposed on existing slums, they fail to acknowledge their existence. When coupled with the multiple planning authorities that plan for these areas, they point to an unknown future and in many cases, potential evictions.

What the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) state

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

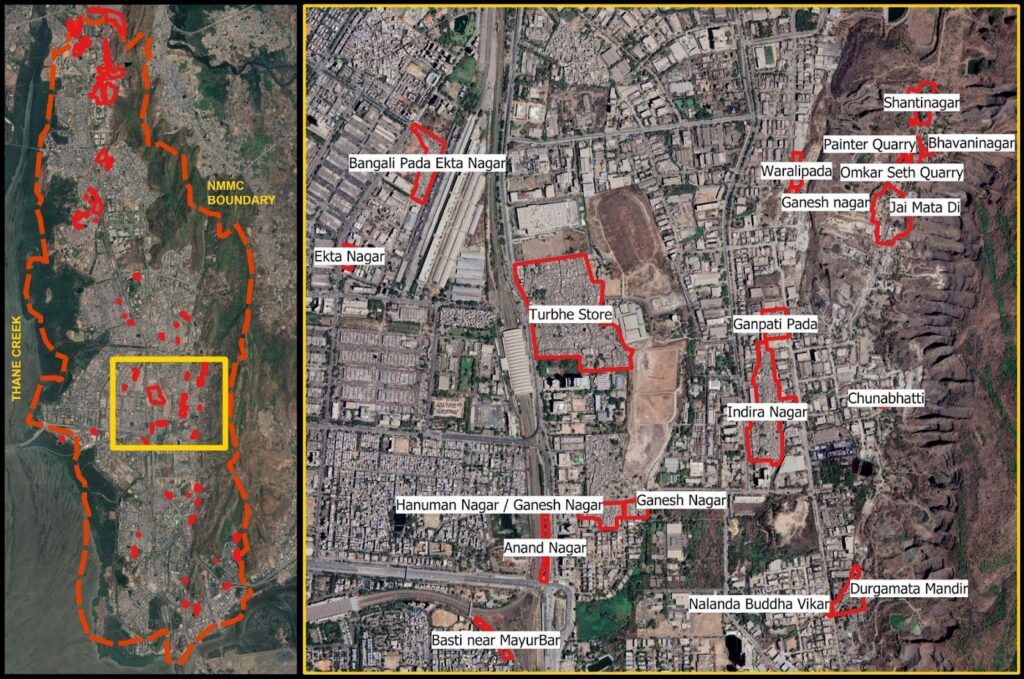

What the proposed land use maps reveal

While the report has relied on the 2011 Census list that lists 47 slums within Navi Mumbai; of the 47 only 11 slums (23%) are within the jurisdiction of the NMMC planning boundary. Of bigger concern is that only 4 slums in the Vashi-Turbhe area (Turbhe Stores, Indira Nagar (part), Ganpati Pada, Warli Pada, Hanuman Nagar) are on land belonging to the state government. 36 slums are on land belonging to MIDC and CIDCO. Of the 76 slums identified in the 2022 YUVA-GHSS survey, only 28 lie in the NMMC planning area. Given that MIDC and CIDCO are Special Planning Authorities, the future of the majority of slums in the city remains in limbo.

An analysis of Proposed Land Use reservations on areas occupied by slums reflects the invisibilisation of slums — 48.7% area of slums are reserved as residential, 13.8% area of slums are reserved as forest, 13% area of slums are reserved as PlayGround and Recreation, 10.3% area is reserved as proposed roads. Further details are in Table 1. The ‘Slum Improvement Zone’, has not been included as a land use category in the proposed land use maps. The broad residential reservation in the proposed land use maps does not delineate this as a sub category.

When reservations are superimposed on existing slums, they fail to acknowledge their existence. When coupled with the multiple planning authorities that plan for these areas, they point to an unknown future and in many cases, potential evictions.

What the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) state

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

While ostensibly these are useful aims, these ideals and ideas unfortunately quickly seem to dissolve in the proposed land use maps.

What the proposed land use maps reveal

While the report has relied on the 2011 Census list that lists 47 slums within Navi Mumbai; of the 47 only 11 slums (23%) are within the jurisdiction of the NMMC planning boundary. Of bigger concern is that only 4 slums in the Vashi-Turbhe area (Turbhe Stores, Indira Nagar (part), Ganpati Pada, Warli Pada, Hanuman Nagar) are on land belonging to the state government. 36 slums are on land belonging to MIDC and CIDCO. Of the 76 slums identified in the 2022 YUVA-GHSS survey, only 28 lie in the NMMC planning area. Given that MIDC and CIDCO are Special Planning Authorities, the future of the majority of slums in the city remains in limbo.

An analysis of Proposed Land Use reservations on areas occupied by slums reflects the invisibilisation of slums — 48.7% area of slums are reserved as residential, 13.8% area of slums are reserved as forest, 13% area of slums are reserved as PlayGround and Recreation, 10.3% area is reserved as proposed roads. Further details are in Table 1. The ‘Slum Improvement Zone’, has not been included as a land use category in the proposed land use maps. The broad residential reservation in the proposed land use maps does not delineate this as a sub category.

When reservations are superimposed on existing slums, they fail to acknowledge their existence. When coupled with the multiple planning authorities that plan for these areas, they point to an unknown future and in many cases, potential evictions.

What the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) state

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The report goes on to acknowledge a deficit of 92,084 houses as per the city’s population in 2011 and notes the need for a housing stock to meet the needs by 2038. In particular it refers to the emerging needs of those living in slums, gaothans, gaothan expansion areas and old buildings. It mentions the need for redevelopment and the need to have reasonable levels of amenities. It notes that this requires an increase in urban land for housing and also policies to create more housing stock. It states that this is taken care of in the present Development Plan. The report also delineates a proposed land use reservation for ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ on 0.9% of the city’s land measuring 0.98 sq km.

While ostensibly these are useful aims, these ideals and ideas unfortunately quickly seem to dissolve in the proposed land use maps.

What the proposed land use maps reveal

While the report has relied on the 2011 Census list that lists 47 slums within Navi Mumbai; of the 47 only 11 slums (23%) are within the jurisdiction of the NMMC planning boundary. Of bigger concern is that only 4 slums in the Vashi-Turbhe area (Turbhe Stores, Indira Nagar (part), Ganpati Pada, Warli Pada, Hanuman Nagar) are on land belonging to the state government. 36 slums are on land belonging to MIDC and CIDCO. Of the 76 slums identified in the 2022 YUVA-GHSS survey, only 28 lie in the NMMC planning area. Given that MIDC and CIDCO are Special Planning Authorities, the future of the majority of slums in the city remains in limbo.

An analysis of Proposed Land Use reservations on areas occupied by slums reflects the invisibilisation of slums — 48.7% area of slums are reserved as residential, 13.8% area of slums are reserved as forest, 13% area of slums are reserved as PlayGround and Recreation, 10.3% area is reserved as proposed roads. Further details are in Table 1. The ‘Slum Improvement Zone’, has not been included as a land use category in the proposed land use maps. The broad residential reservation in the proposed land use maps does not delineate this as a sub category.

When reservations are superimposed on existing slums, they fail to acknowledge their existence. When coupled with the multiple planning authorities that plan for these areas, they point to an unknown future and in many cases, potential evictions.

What the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) state

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The vision of the development plan, outlined in the report, is to achieve participative, stakeholder-friendly, growth-driven development and create ‘citizen-oriented’ policies. Among its 11 objectives, it clearly outlines minimising inequality, creating more housing stock that is within the reach of the common man and providing for redevelopment of slums.

The report goes on to acknowledge a deficit of 92,084 houses as per the city’s population in 2011 and notes the need for a housing stock to meet the needs by 2038. In particular it refers to the emerging needs of those living in slums, gaothans, gaothan expansion areas and old buildings. It mentions the need for redevelopment and the need to have reasonable levels of amenities. It notes that this requires an increase in urban land for housing and also policies to create more housing stock. It states that this is taken care of in the present Development Plan. The report also delineates a proposed land use reservation for ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ on 0.9% of the city’s land measuring 0.98 sq km.

While ostensibly these are useful aims, these ideals and ideas unfortunately quickly seem to dissolve in the proposed land use maps.

What the proposed land use maps reveal

While the report has relied on the 2011 Census list that lists 47 slums within Navi Mumbai; of the 47 only 11 slums (23%) are within the jurisdiction of the NMMC planning boundary. Of bigger concern is that only 4 slums in the Vashi-Turbhe area (Turbhe Stores, Indira Nagar (part), Ganpati Pada, Warli Pada, Hanuman Nagar) are on land belonging to the state government. 36 slums are on land belonging to MIDC and CIDCO. Of the 76 slums identified in the 2022 YUVA-GHSS survey, only 28 lie in the NMMC planning area. Given that MIDC and CIDCO are Special Planning Authorities, the future of the majority of slums in the city remains in limbo.

An analysis of Proposed Land Use reservations on areas occupied by slums reflects the invisibilisation of slums — 48.7% area of slums are reserved as residential, 13.8% area of slums are reserved as forest, 13% area of slums are reserved as PlayGround and Recreation, 10.3% area is reserved as proposed roads. Further details are in Table 1. The ‘Slum Improvement Zone’, has not been included as a land use category in the proposed land use maps. The broad residential reservation in the proposed land use maps does not delineate this as a sub category.

When reservations are superimposed on existing slums, they fail to acknowledge their existence. When coupled with the multiple planning authorities that plan for these areas, they point to an unknown future and in many cases, potential evictions.

What the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) state

The Maharashtra Unified Development Control Promotion Regulation applicable to the NMMC planning area includes various forms of seemingly progressive housing options such as Inclusive Housing, Social Housing (Rental housing), Affordable Housing for EWS/LIG, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana for EWS/LIG. It also details the ‘Slum Improvement Zone’ as being included within ‘Residential R-1’ land use reservation and notes that it shall be developed as per the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme of the Maharashtra Slum Act (Ibid.).

The CIDCO DCRs for Navi Mumbai (1975), amended in 2016 for CIDCO areas, applicable to the CIDCO planning areas and plots, do not outline any clear provision for slum upgradation or rehabilitation. The MIDC DCRs (revised 2009) applicable to the MIDC planning areas, includes basic provisions on formal housing for industrial workers. Both DCRs however refer to ‘Group Housing Scheme’ and ‘Plotted Development Scheme’. These appear that they could allow for a body like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority, however clear rules for slums have not been spelt out. A 2020 GR however, does include SRS on Navi Mumbai and CIDCO land.

Through the UDCPR regulations for slums, one thing clear is that slum redevelopment and resultant slum TDR to be earned in the process, is a state wide tailor-made solution for existing slums that meet the cut-off date.

Ambiguous governance boundaries and land contestation

Powers as planning authority were delegated to NMMC partly in 1994 and 2008 when CIDCO handed over select plots to the NMMC. In 2017 CIDCO was appointed as Special Planning Authority (SPA) for select areas. Similarly, the MIDC is the SPA for the industrial areas. This shift of authorities has been gradual and coupled with land contestation, with CIDCO, MIDC and NMMC in the powerplay.

In the context of the draft DP, the proposed plan thus only considers planning for 7 nodes in the NMMC boundary, while the rest of the land parcels are viewed as separate domains. This not only excludes a large population residing in these areas but it also exacerbates the anxieties for their future. As a result, the urban local body (NMMC) which is deemed to develop a cohesive DP for the region, has excluded large parcels of land resulting in a disjunct planning proposal.

An analysis of planning areas shows that MIDC currently accounts for 17% (approx 25 sq km) of Navi Mumbai while CIDCO accounts for large swathes measuring 10 sq km and many smaller plots within nodes. This percentage is high — the report mentions 975 plots that are yet to be handed over to NMMC and that 90% of land in Navi Mumbai is owned by CIDCO. During the preparation of the current DP that began in 2017, the Urban Development Department and CIDCO have raised concerns regarding the plan. As per objection raised by CIDCO, the Government of Maharashtra issued directions to NMMC in 2021 not to propose reservation on any plot owned by CIDCO measuring more than 500 sq.m.

This complexity has had severe repercussions on slums that lie on these ambiguous land boundaries. Most households in slums exist on insecure tenure and lack formal land documentation, in spite of having existed for decades. Land contestations interfere with people’s efforts to gain any form of formal documentation from authorities. This land division has furthered what Shirish Patel, one the chief architects of Navi Mumbai, terms as the ‘balkanisation of planning’ where no single authority is able to holistically plan for a city. Perhaps in such situations, in the guise of ambiguity, it becomes convenient for the authorities to side-line issue of the urban poor.

Ways forward

As the future for India’s largest planned city is being decided for the next two decades, it needs to acknowledge its present. The development plan 2018–2038 is about people who have come to inhabit the city. There must be a participative, inclusive process that acknowledges the contribution of thousands of workers who have built and continue to sustain it. It must account for their habitats by counting the numbers of slums accurately, reserve land occupied by existing slums under the ‘Slum improvement zone’ reservation or under a ‘Public Housing’ reservation where there must be options for self-development and upgradation, beyond the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme that has not seen much success at creating adequate habitats. It must include options for rental housing for migrant families.

If Navi Mumbai is to continue to show Indian cities the way to develop and be an inspiration to further endeavours in planning, it must showcase a way to include slums and the needs they represent even in planned cities. Navi Mumbai must chart its own plan, its own future, just like it did 50 years ago. Most importantly, its elected body must be given the power to do so.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]