YUVA at Vidhi’s ‘Up the Ante’ Episode 3

When agency shifts, so does the trajectory of urban development

Mumbai has encountered multiple visions for its future, from a “world-class city (by 2013)” to a “climate resilient city (by 2050).” However, recent headlines—inflation hikes, local protests, and infrastructure failures—highlight the need for an open dialogue about the systems and processes impacting the quality of life of its inhabitants. Issues of inclusion, participation, access, and ownership remain unaddressed in many of Mumbai’s communities. Growing urban injustices—stark inequalities, disproportionate environmental burdens, and uneven access to opportunities—calls for a renewed search for ideas and solutions.

Up the Ante is a series of conversations that confront systemic injustices and socio-economic inequalities in cities, hosted by Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Building on earlier discussions about housing rights and the impact of infrastructure projects on the environment and citizen groups, its third episode segued into the concerns of marginalised youth in the city. Moderated by Yeesha Shriyan, the session featured the following speakers:

- Asma Ansari, a Senior Leader of the Malvani Yuva Parishad youth collective, who shared powerful instances of youth-led changemaking at the basti (informal settlement) level.

- Sachin Nachnekar, Programme Lead, who highlighted YUVA’s journey of forging multiple youth collectives across the city.

- Roshni Nuggehalli, Executive Director, YUVA, who provided a broader perspective on institutionalising youth participation through the lens of legality.

Growing up in a basti in Mumbai

The discussion began with Asma sharing her lived experiences growing up in the city. Born in Bihar, she moved to Mumbai at the age of four. Her family initially settled in Kandivali but was displaced due to developmental work. Her father then relocated the family to Ambujwadi in Malad. Asma was shocked upon arrival, seeing people living in makeshift tarpaulin houses, struggling daily for water, and with no areas for children to play. Adjusting to her new life and surroundings was hard. She held onto the hope of moving to a better, more livable neighbourhood.

Cut to the present day, Asma continues to live in Ambujwadi. Her hope to escape faded into a gradual acceptance which, over time, evolved into a powerful sense of agency. She emerged as a first-generation youth leader and has been at the forefront of driving change in her community.

Asma voiced her frustrations about basti residents being seen as mere vote banks. “We exercise our right and responsibility of voting, but promises made during the elections are never fulfilled,” she said. Refusing to feel helpless in their situation, the youth in Ambujwadi initiated a self-determined search for spaces for their play and leisure. Through advocacy and clean-up drives, they converted auto parking areas and derelict lots into multifunctional, safer, and more accessible spaces.

However, these spaces were still male dominated. The next step was bringing girls out of their homes and onto the field through the “Hum Bhi Hain Maidan Mein” (We Are Also In The Field) campaign. Playing in front of families and community members was met with reluctance, so they started holding matches in places outside or around the basti. It was a gradual process of gaining the courage to play in front of their families. Although there are still no dedicated open spaces or parks in Ambujwadi, the girls ensure they continue to participate, reclaiming their right to play and asserting their presence in the community.

Such instances stand as a testament to the critical role of informed and active youth in shaping their own futures. “Witnessing other young girls’ growth and milestones is what inspires me to continue working and include more youth in leading changemaking initiatives,” Asma said.

Victory for the youth collective lies in seeing multiple generations of leaders take over the processes and transform the identity and workings of the group over time. This approach ensures sustainability across generations, preventing leadership power from being concentrated in the hands of a few. Asma added, “Change is a natural process—as new members join, the identity of the collective evolves. Instead of resisting it, our philosophy is to invite and embrace change.”

Channelising the collective strength of young people

Sachin explained YUVA’s youth processes, beginning with a poignant question: “We keep saying ‘Mumbai meri jaan hai,’ but where is our participation in the city?” YUVA works to empower young people and build their leadership capacities, so they can drive change themselves. Coming from a basti himself, Sachin has worked his way out and sees the potential for youth to unite, form collectives, and present their concerns to the government.

Youth groups from bastis develop a unique identity by organising and participating in activities they enjoy. Once this identity is established, they map their community to identify spatial and social issues. The aim is to better understand their locality, comprehend the governance landscape, and hold authorities accountable at various levels.

To tackle the non-provision and maintenance gaps of civic amenities, the youth reach out to government stakeholders, such as the local police station or the nagarsevak office, via letters or in person meetings. To engage with urban planning issues, they read, understand, and provide feedback on the Development Plans. To have an active say in policymaking, they carefully review policy drafts directly affecting the youth, such as the recent National Youth Policy, and submit objections and suggestions.

Through value-building activities and exposure visits, these youth groups connect with values like gender equality and environmental justice. They counter issues such as eve teasing, substance abuse, and unsafe spaces by organising clean-up drives, claiming spaces, and creating nurturing environments. There is also a strong focus on promoting gender mainstreaming by creating maidan spaces for neutral games like lagori to encourage girls to play.

Sachin also highlighted YUVA’s “City Caravan,” a course designed to equip young people with the leadership skills needed to participate in urban governance. The course consists of modules on urbanisation, governance, advocacy, and strategies for making cities inclusive. It also teaches participants how to conduct social audits. A significant focus of the course is the 74th Amendment Act, which emphasises decentralisation and the strengthening of local governance. By understanding the roles and responsibilities of Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) in cities, the youth learn how to improve accountability and advocate for their communities effectively.

Through these practices, youth collectives have successfully addressed small but significant issues in their communities, fostering a sense of ownership and encouraging more young people to join the movement. This growing engagement has powered the process to continue, creating a ripple effect of active, informed, and empowered youth leaders committed to driving change in Mumbai.

Yeesha Shriyan asked, “ How does YUVA make urban planning concepts palatable for young people?”. Sachin explained that it is an intentional process which entails translations from English to Marathi and Hindi, simplifying legal terminologies, demonstrating maps and land use plans, and explaining the meaning of different colours and terms such as reservation areas and their implications on people’s lives.

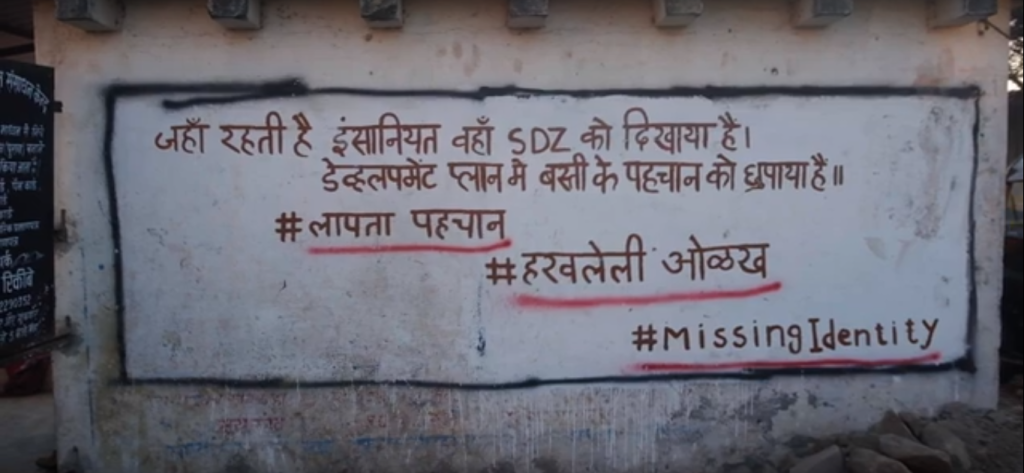

Sachin shared an example of the Laapata Ambujwadi campaign initiated by the Malvani Yuva Parishad youth collective. In the draft development plan, Ambujwadi was classified as a No Development Zone (NDZ), leaving its residents vulnerable to recurring evictions and demolitions. To combat this, the youth employed creative methodologies, including street plays, to inform the community about the potential impact of this classification on their futures.

They collected complaints and submitted them to the planning department, demonstrating strength in numbers. Their efforts culminated in a significant victory: Ambujwadi’s classification was changed to a Special Development Zone (SDZ), which is not without its problems but overall secures more stable and secure living conditions for its inhabitants.

Institutionalising youth participation in cities

Roshni discussed the institutionalisation and scaling up of youth participation processes, emphasising the concept of citizenship as a paradox in cities. She highlighted that while individuals are legally recognized as citizens, many lack substantive citizenship rights such as documentation, access to water, sanitation, street lighting, and open spaces—especially in marginalised communities. This gap between legal status and substantive rights underscores the importance of individual and collective agency in constructing meaningful citizenship.

Roshni pointed out that the 74th Amendment Act provides a direct pathway to achieving these rights and strengthening citizenship. She advocated for reforms like the Nagar Raj Bill, or the Community Participation Law, which seeks to include all individuals, regardless of privilege, in urban governance discussions—a space often considered exclusive and elitist.

She noted the role of Mohalla Samitis in grassroots practice but highlighted their limited legal recognition. Roshni proposed the establishment of youth councils within elected bodies (read: National Youth Council in Brazil) as a crucial step toward integrating youth perspectives into urban governance on a broader scale. While these efforts currently occur piecemeal, she underscored the foundational importance of the 74th Amendment Act in driving systematic change.

Roshni advocated for youth mainstreaming, i.e. viewing policies like the National Urban Livelihoods Mission (NULM) and the National Youth Policy (NYP) through a youth-focused lens. This shift in discourse, she argued, is essential for aligning policies with the realities and aspirations of young people, thereby fostering inclusive urban development and governance.

Sachin added, “Youth policies should originate from the youth themselves, but this is not happening. Pertinent challenges such as mental health and employment are not being adequately addressed.”

Where we go from here

The conversation flowed with insights drawn from personal experiences and professional expertise, making evident the nuanced ways in which young people can and should be engaged in urban governance, planning and policymaking processes.

What came through was that fostering youth participation hinges on equipping them with baseline awareness of urban plans and policies. Forming and running youth collectives in bastis democratically through sustained engagement has proven that people are best equipped to tackle their own challenges. Creating safe spaces for and by the youth that encourage dissent and critical thinking across spheres of family, community, city, and larger society are crucial steps forward.

As the event drew to a close, a boy from the audience shared that he is part of a local youth collective from Colaba’s Geeta Nagar basti but they operate on a fairly small scale. Inspired by YUVA’s processes, he was curious about carrying out similar changemaking initiatives in his basti. Such spaces – where ideas are shared unfiltered and curiosities are welcomed – are the start of something big.