A people’s conversation on climate, justice, and the future we want!

When we walk through Vasai–Virar, signs of a changing climate are increasingly visible: the flooded streets, hotter summers, vanishing wetlands, and roads that seem to disappear every monsoon. But for most residents, climate change is not an abstract idea. It is part of daily life.

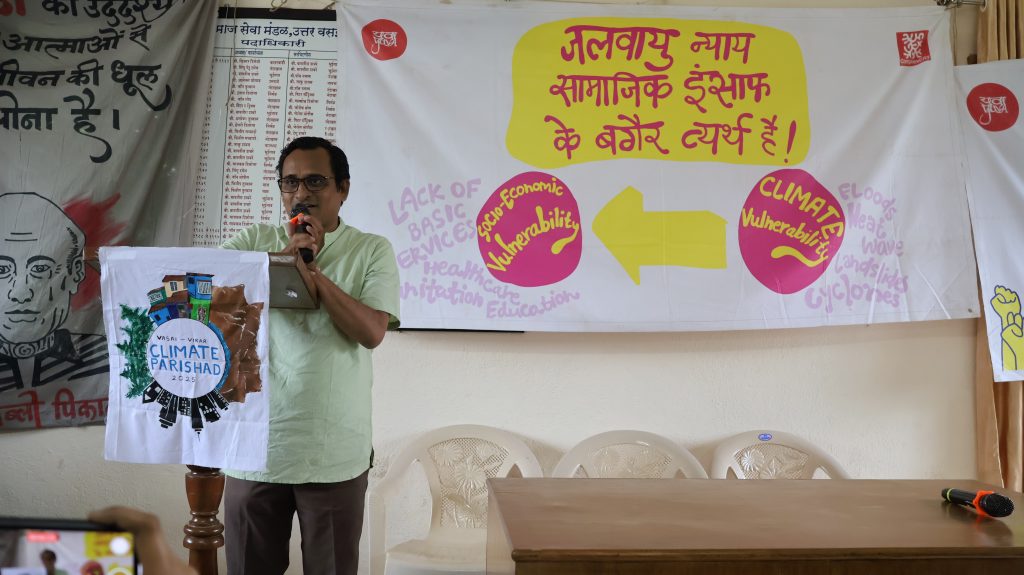

This is why the Vasai–Virar Climate Parishad 2025 was held: a space where people could come together, share their lived experiences, and build a collective plan for a just and resilient future. Over 23–24 August 2025, residents from bastis, gaothans, Adivasi settlements, youth groups, women’s collectives, farmers, waste pickers, climate educators, experts, and local leaders gathered in the same room to map climate risks, discuss the city’s growing challenges, and come to the solutions grounded in people’s everyday realities.

Day 1: Mapping Our Climate Realities

Climate change is not far away. We live it every day!

The Parishad opened with a grounding reminder by YUVA and AVAV facilitators: Vasai–Virar is already experiencing the climate crisis. Flooding, unmanaged waste, heatwaves, poor infrastructure, and disappearing green spaces are shaping people’s daily struggles.

Before people began telling their stories, YUVA shared simple maps and local data so everyone could see the patterns clearly. The team geo-tagged over 100 bastis across Vasai–Virar (over 100 in total), and the maps showed three urgent concerns : where water collects and floods most often (a central axis of hotspots), where land is slipping and at risk of landslides (notably around Nalasopara), and where heat is highest, with some neighbourhoods recording significantly higher temperatures The slides also showed how wetlands and mangrove areas are being built over or used as waste sites, and that there are almost no air-quality monitors near the places that need them most. These facts showed one clear thing: the places facing the biggest risks are the same places where people already struggle. Protecting nature and planning with communities can help prevent many of these problems.

An engaging session on Participatory Climate Risk Mapping followed, where residents marked flooding spots, heat pockets, garbage dumping points, and unsafe spaces for women. Youth shared how extreme heat disrupts their studies and livelihoods.

Through these maps, people could clearly see what they already experienced every day, that bastis and the nearby neighbourhoods face the biggest impacts.

What People Said: Voices from the Ground

The later sessions brought stories from residents, helping everyone understand how climate impacts daily life in Vasai–Virar.

Poonam Vishwakarma, who has lived in Vasai–Virar for over a decade, shared her experience of the everyday challenges she continues to face: “I’ve lived here for 12 years, but honestly, nothing’s improved, not the roads, not the water, not even health care. Women work all day… and still barely earn enough to get by.”

Her reflection pointed to the intersection of inadequate services and climate vulnerability and development must begin with basic dignity and reliable services.From the youth, Anshu Gupta, a young climate educator with YUVA, spoke about the growing role of young people in shaping awareness at the grassroots. “As climate educators, we take what we learn and bring it to the people who need it most… helping communities understand climate change and start acting together.” The reflection highlighted how knowledge becomes powerful only when it reaches the most vulnerable neighbourhoods.

Another youth leader, Raj Jaiswal, described the difficulties his community faces during the monsoons: “During the monsoon, the streets flood and kids can’t get to school… even reaching a hospital seems impossible. If we don’t act now, it will get far worse.” His words underlined how climate hazards interrupt daily routines, education, health, and livelihoods, things many people take for granted.

Representing the voices of waste pickers, Sunita Bagula brought attention to the challenges faced by women workers: “The roads are so broken that for women like us, even stepping out is a struggle. There aren’t enough toilets, the water is dirty, and many of us still can’t find fair-paying work. For women ragpickers, it becomes harder because sharp objects are often thrown into the garbage and injure our hands. We request everyone to separate wet and dry waste.” Her experience reflected how climate risks deepen the struggles of women who deal with unsafe surroundings and fewer livelihood options.

A local resident speaking about water scarcity expressed the core of the struggle in one simple line, saying, “Water is power. If you have water, you have independence… if you don’t, you depend on every system and politician.” It captured how water shortages shape not only health and daily comfort but also people’s autonomy and sense of control.

Adivasi leader Shashi Sonawane spoke openly about the unequal cost of development: “All the talk of development gets measured in cement and steel. The real cost falls on Adivasis and workers. We don’t want palaces, just good roads, drinking water, and schools.” His words revealed the long-standing gap between grand infrastructure promises and the basic needs of communities that are most impacted. He added another saddening truth: “When the city floods, we don’t get rich soil, we get urban filth pouring into our homes. If we keep ignoring nature, our children will never know a natural life.” This reflection brought attention to how environmental damage, pollution, and unplanned construction combine to worsen climate risks.

Together, these voices showed that the climate crisis cannot be separated from social justice. The stories shared in the room made it clear that any climate solution must first recognise people’s lived realities, because those facing the harshest impacts already know what the city needs most.

Urban Planning and Climate Governance: Challenges and Hope

The panel on Urban Planning and Climate Governance brought together experts, planners, and government representatives who reflected on the urgent need to rethink how Vasai–Virar plans its future. Maharashtra’s State Climate Action Cell explained that many climate plans failed due to lack of information, but because they are created without truly involving the communities who face climate impacts every day.

Urban designer Anirudh Paul emphasised that the city’s climate future will be shaped by the decisions taken today, how development plans are made, how land is used, how transport systems are designed, and whether wetlands and ponds are protected or lost. These choices, he stressed, will determine whether the city becomes more resilient or more vulnerable.

YUVA’s leadership, including Roshni Nuggehalli, reminded everyone that climate resilience cannot be built through policies alone; it requires real partnerships between planners, government bodies, and the people whose lives are directly affected. The day came to a thoughtful end with a cultural performance that used humour, songs, and storytelling to ask difficult yet essential questions: Who really carries the burden when floods and heatwaves strike? The performance sparked conversations on who bears the greatest burden from climate impacts, walking away with more questions than answers, but also with a stronger shared sense of responsibility towards the city’s climate future.

Day 2: Reimagining a Just Climate Future

Connecting Global Climate Goals to Local Realities

Day 2 began with a focus on connecting global climate goals to the everyday realities of Vasai–Virar. Facilitator Dulari Parmar explained India’s climate commitments: mitigation, adaptation, loss and damage, and just transition, in a way that made sense to the community. She showed how ideas often discussed at international forums turn into practical actions on the ground: affordable cool roofs that reduce indoor heat, flood shelters located within informal settlements where they are truly needed, green jobs that can support women and informal workers, and the protection of mangroves as part of addressing loss and damage. Her message was consistent, climate action becomes meaningful only when people participate in shaping it.

The session then moved into learning from other cities, with facilitators sharing the experience of Ambojwadi in Mumbai, where residents and authorities jointly created a Community Climate Action Plan. Through collective effort, they identified flood pathways, fixed drainage systems, strengthened housing, and set up community monitoring mechanisms. This example showed that practical and lasting climate resilience emerges when communities and governments plan together.

Building Vasai–Virar’s People’s Climate Action Plan

During the collective discussion on Day 2, people spoke about the issues that affect their daily lives and the kind of city they hope Vasai–Virar can become. Water emerged as the most urgent concern.

A participant said simply, “If we don’t drink water, we die. If we drink water, we die.” Memories of the 2018 floods resurfaced as residents spoke about how the city moves between heavy flooding and severe water shortage. They suggested practical steps such as reviving the holding ponds once planned by CIDCO, protecting wetlands that naturally hold excess rainwater, and ensuring drains are desilted before every monsoon.

Air quality and mobility were also discussed, with residents linking traffic congestion and rising pollution to everyday health problems. They spoke of the need for more buses, better last-mile connectivity to remote settlements, greener public spaces, and greater awareness about how urban design influences air quality. Many felt that improving mobility would not only reduce emissions but also make the city more livable.

Concerns around health and education were voiced strongly. Participants questioned why, despite “millions collected through education tax, Vasai–Virar still does not have adequate municipal schools.” One resident asked, “If our children must go to Mumbai for hospitals or schools, what does that say about our city’s priorities?” Their reflections highlighted the link between basic services and climate resilience, especially in a fast-growing city.

Young people and farmers spoke passionately about shrinking wetlands and the loss of biodiversity. They described how vanishing wetlands affect migratory birds, local ecosystems, and even the city’s ability to handle heavy rains. Suggestions included organising community Nature Days, securing legal protection for wetlands, encouraging rooftop gardens, and ensuring drinking water points for workers during extreme heat.

The discussion also touched on accountability and transparency, with many expressing frustration that official reports are often inaccessible and that planning decisions feel distant from people’s needs. One participant summed it up: “Research stays locked away in files. We need participatory plans built from the ground up.” Residents called for ward-level committees, youth involvement, and regular citizen monitoring to ensure planning processes remain open and accountable.

What The Parishad Taught Us

In the closing reflections, participants shared thoughtful concerns about the future of the city. One person said, “Just as we think about our children’s future, we must think of our city’s future.” Another added, “How will Vasai survive if its water and forests are not protected? Development cannot mean drowning our villages in concrete.” The most urgent reminder came from those who spoke about preventable tragedies: “Every year, people die because of falling electricity wires during the rains… Who is accountable?”

These reflections showed how deeply residents care about their city, and how climate resilience, basic services, and social justice must move forward together.

Resources & References: