Introduction

UNICEF defines social protection as ‘a set of policies and programmes aimed at preventing or protecting all people against poverty, vulnerability and social exclusion throughout their life-course, with a particular emphasis towards vulnerable groups.’ This specific conception of social protection is aspirational, since social protection systems in most countries do not yet measure up to these expansive criteria. For example, this conception has both specificity (‘particular emphasis towards universal groups’) and universality (‘all people’). Additionally, the protection is to cover the complete duration of a person’s life-cycle as opposed to piecemeal protections against only a select adverse events, vulnerabilities or exclusions. Lastly, this formulation conceives protection from not just poverty and vulnerabilities, but from social exclusion as well, which calls for specific safeguards to be built in the social protection system.

The importance of progressively moving towards a social protection system which is comprehensive (encompassing the complete life-cycle), universal and inclusive became more apparent during the Covid-19 pandemic. The Union and the State governments attempted to shield citizens from the unprecedented disruption caused by the pandemic and lockdowns, through a mix of reformulation of existing social protection programmes (like provisioning of grains under the targeted public distribution system, increasing cash transfers, etc.) as well as through introduction of ad hoc, one-time relief measures. Evaluations of these measures revealed the several layers of exclusion that haunted the existing system of social protection in the country. The most stark illustration of these exclusions was the plight of migrant workers who couldn’t access most of the relief and support measures, and were thus forced to undertake risky and desperate journeys back home. The idea of Social Protection Facilitation Centres was born out of the lessons learnt from this experience.

Social Protection Facilitation Centres

To address access-related challenges, a model of facilitation centres as hubs reaching out to residents communities living in proximate areas was implemented by YUVA in collaboration with UNICEF-Maharashtra. Three model Social Protection Facilitation Centres (SPFCs) were rolled out across diverse locations in Maharashtra: Panvel, Raigad district (urban, peri-urban); Kagal, Kolhapur district (rural) and Chikhaldara, Amravati district (tribal). Between August 2021-October 2023, the SPFCs were able to reach 247 villages across 151 Gram Panchayats and 25 low income settlements across 1 ULB (Panvel Municipal Corporation) across the 3 blocks in these districts.

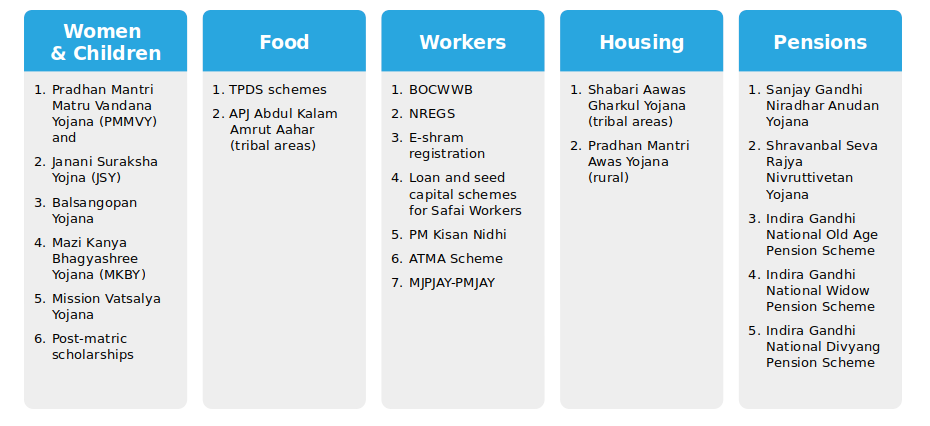

To understand the existing levels of access, and the nature of impediments faced by the target groups, district-wise Rapid Assessments of Social Protection Schemes were carried out. These assessments helped us identify 22 schemes and programmes which had the greatest potential in terms of making an impact in the lives of the vulnerable groups.

Facilitating Access to Existing Schemes

The reasons for low levels of access to these schemes, as revealed by the assessment, included: low-levels of awareness about existing schemes and the procedure to access them and lack of necessary identity documents. These proximate causes were compounded by low-levels of literacy and remote geography (poor connectivity, access etc). Hence, the first task taken up by the SPFCs was creating awareness about the selected schemes and programmes, through development of easy to understand material and organising village/settlement-level camps, sessions and meetings. Over 450 meetings, camps and sessions were organised across the three SPFCs during the period August 2021-October 2023

The above awareness generation activities drew people to the SPFCs, where the staff determined the eligibility of the members for the existing stack of schemes and provided hand-holding support in preparing necessary documentation, in partnership with district-level officials, CSCs, post offices, banks and ward officials. Between August 2021-October 2023, a total of 4,351 applications for identity documents were filed and sanctioned across the three SPFCs.

The next step in facilitation was assistance in filing of applications, since most vulnerable members found it daunting to comprehend the elaborate procedures. The model SPFCs facilitated filing of both physical and online applications. In all, a total of 12,627 applications for social protection schemes and identity documents were filed across the three SPFCs during a 26-month operating period i.e. over 175 applications were filed at each centre every month.

The last albeit the most crucial step was ensuring that these applications were sanctioned without inordinate delays. One of the reasons for disinterest among the vulnerable communities towards accessing social protection schemes was the multiple trips to the offices required to get the applications approved. Through regular meetings with block and taluk-level officials and persistent follow-ups, the SPFCs were able to achieve high success rates in terms of sanctioning of applications and disbursal of entitlements, and also the time taken for the process. Of the total applications filed, 10,247 applications were sanctioned, at a sanctioning rate of over 81%. In the process, cash entitlements amounting to INR 2,04,68,169 were received by applicants, a large part of which coincided with the difficult post-pandemic phase for most of the communities.

Advocacy for Enhancing Access

Going beyond facilitation, the SPFCs advocated with the relevant authorities for relaxation of eligibility criteria and documentary requirements as well as simplification of procedures where the existing norms were leading to exclusions. For example, to access old-age pensions, the age of the applicant had to be validated in government hospitals, adding another layer of complexity to the process. Through rapport-building with officials, alternatives which didn’t require visit to the hospital were implemented. Similarly, heir certificate, which was a difficult document for widowed women to acquire, was made an optional requirement through district-level advocacy.

Sustaining the Efforts

With the aim of making access to social protection more sustainable, and transitioning to a community-led facilitation process, capacity building efforts were undertaken with civil-society organisations (CSOs)/Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), community-based groups, Mahila Arthik Vikas Mahamandal (MAVIM), Maharashtra State Rural Livelihoods Mission (MSRLM), Gram Panchayats (GPs). These sessions contributed to the uptake of the facilitation services provided by SPFCs, and laid a foundation for devolution of SPFCs to Gram Panchayat level, and expansion of community ownership of the facilitation process.

Evidence-based Policy Advocacy

The evidence generated during the process of facilitating social protection across the SPFCs was collated into policy briefs, which were then used to carry out policy-level advocacy work in the state. To address the lack of an accurate metric to capture the impact of social protection interventions, a framework of Social Protection Scores was devised in collaboration with Fields of View and promoted with the concerned officials through a roundtable discussion. These Social Protection Scores are index-based household-level quantitative measures of the extent of vulnerability. The SPS for a household falls within the range 0-300; 300 points denoting the point where households start becoming vulnerable, and 0 point denoting critical vulnerability. These SPS scores are estimated based on simulation models, which presently account for three dimensions of vulnerability – nutrition, education and finance. These Social Protection Scores allow us to a) gauge the level and nature of existing vulnerability of the household, b) design appropriate interventions based on this understanding and c) evaluate a range of policy options based on their predicted impact on the scores; thus fulfilling an important evidence-gap in social protection policy-making.

Over the period of the last two years, the concept of Social Protection Facilitation Centres has found wide acceptance among the communities which have been served by these centres. In a relatively short span, the SPFCs were able to generate strong demand for the existing social protection measures and ensure high sanction rates through collective advocacy at taluka and district levels. In the process, several policy insights have been generated which if incorporated, can make the social protection system in the state more accessible. Models of social protection facilitation such as SPFCs need to be institutionalised within the wider policy landscape by embedding them within Gram Panchayats and Urban local bodies.