This is the second part of a two-part blog on the challenges being faced by residents of informal settlements in Guwahati in accessing social protection entitlements in absence of Aadhar and the campaign by YUVA to addres these challenges. The first past can be read here.

When a slum is notified by the state government it confers a certain level of security to the settlement. Different states vary in their rules and criteria for notifying a slum. Lack of government recognition, also referred to as “non-notified status” in the Indian context, may create entrenched barriers to legal rights and basic services such as water, sanitation, and security of tenure.

Nearly two lakh people in Assam reside in informal settlements across 31 towns in the State. As per the Office of Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India, the total slum population in Assam stood at 1,97,266. Of the total number of slum dwellers in the state, 9,163 reside in notified slums (notified under any Act), 70,979 in recognized slums (area recognized as slum but not notified under any law), and 1,17,124 in identified slums (congested area which is enumerated as slum under census enumeration despite not being recognised or notified as such) (see Note 1 at the end for details).

Slum redevelopment in any urban center of the country is mostly routed through schemes and policies like Rajiv Gandhi Awas Yojana previously, and now Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana – (PMAY here onwards) which has specific components designated to it. In 2015 the then state government, in a bid to redevelop slums in the city initiated steps to build houses for the slum dwellers under the ‘Rajiv Awas Yojana’. Around 164 slum areas were identified for redevelopment but the scheme never took off beyond the initial planning stage.

YUVA in this context, has been advocating for the rights of slum dwellers in the city who have now waited for 7 years and are yet to see any improvement in their sites of habitation. When the Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC here onwards) was approached regarding the delay in implementation of PMAY in the urban slums of the city, GMC Commissioner said that these slums have to be recognised first. GMC referred us to the Assistant Engineer of the state to get the list of recognised slums, after which they were further sent to the City’s Waste Management Dept. who said that the list has been lost. These bureaucratic hurdles have prevented even the initiation of slum recognition in the state, with no clarity among the different state departments about who is responsible for creating and maintaining a repository of data on slums. But a list was received by the PMAY department in 2017 which listed 164 slums across the city, again this list was not given due consideration for implementing the housing scheme in the city for which the department started their own survey to list out the number of slums in the city. Later through an RTI application, we could find out that only 24 slums have been surveyed by the PMAY–U Assam department in the In Situ Slum Redevelopment (ISSR) category (see Note at the end for details), but no data-sheets were prepared nor were any recorded details found. The PMAY Assam Mission Director, stated that the sole reason behind the non-implementation of the ISSR component was non-notification of the slums in Guwahati. And due to these non-notified status, the settlements are forcefully demolished, no basic services provided such as electricity, water, road connectivity and housing being a major challenge for the residents to live a dignified life.

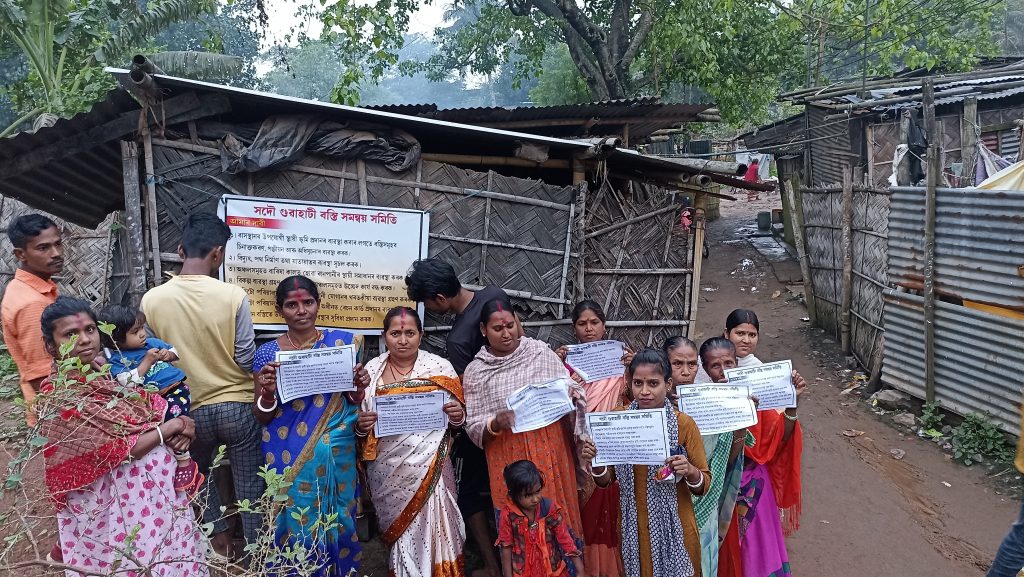

In 2021, the All Guwahati Slum Coordination Committee was formed to advocate for the rights of slum dwellers in the city, resist forced evictions, demand recognition of the slums, and basic services for slum residents. The coordination committee also led a campaign before the Guwahati Municipal Elections in April 2022, to advocate for these rights through mobilizing the community leaders and campaign in each community, capacitating the people to build their confidence in raising questions in front of contesting candidates, prepare a banner with the demands of the communities and tug it in each of the community entrance, distributed leaflet with demands, shared a memorandum to each candidate of the wards and share an appeal to the civil society to support the demands of the community people. The demands were notification of the slums, putting a stop to forced evictions and drafting of a rehabilitation and resettlement policy, provision of access to basic services such as water, electricity, road connectivity and providing drainage to reduce flash floods in the communities.

Image 1: Community Meeting of the All Guwahati Slum Coordination Committee

There are several non-notified informal settlements in Guwahati city where even basic services like electricity are inaccessible. One such settlement is Babu Basti in Narengi where residents have been staying for close to 30 years now. There is a railway track for goods trains that passes through the Basti which passes through two other settlements – Lala Basti and Dharmanagar, Babu Basti being in the middle of these two. The railway track is used sporadically to transport goods and connects to Oil India. While residents in Lala Basti and Dharmanagar have electricity connections, Babu Basti with 35 households in the middle has been without electricity for years now.

When residents of the settlement demanded this basic service, the electricity department in the city cited logistical challenges in bringing the connection to that locality. They demanded a sum of INR 20,000 in 2014 from all the residents to cover the cost partially, most residents complied and paid the amount. But till 2018 when YUVA initiated work with the communities in this area, no work had started to set up electrical lines.

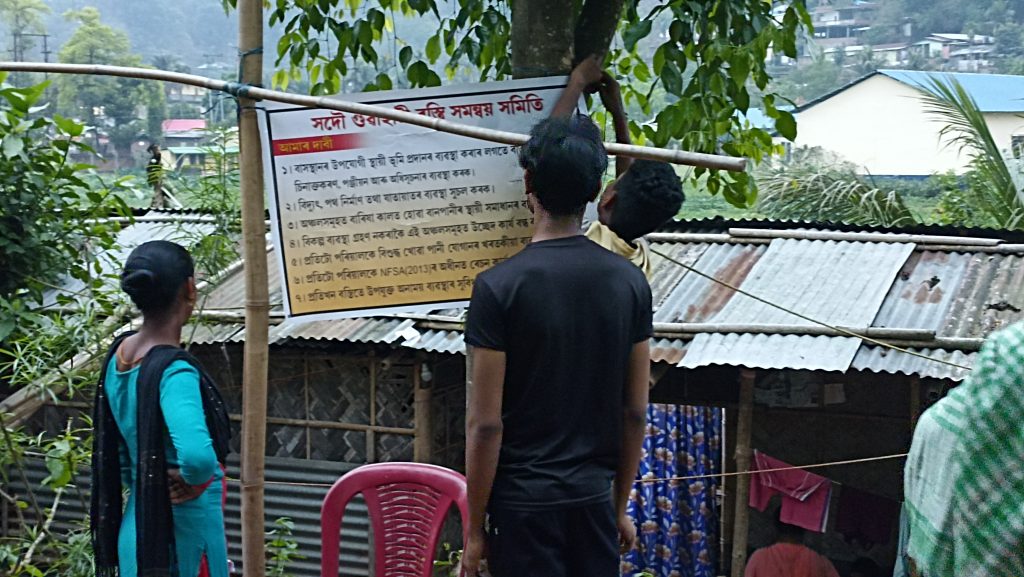

Image 2: Campaign carried out by All Guwahati Slum Coordination Committee

In 2019, a circular issued by the Assam Government said that every household in Assam will be electrified, with the only document required to be furnished being land documents. For those without land documents, an affidavit from the court has to be produced to meet the eligibility. All these requirements for the application were ready by February 2020, i.e before the first wave of the pandemic and the lockdown.

In August 2020, all the application forms of residents from Babu Basti with all the required documents were submitted to the electricity department. The next step according to the protocol was a ground-level survey by linemen. But by November there had been no survey conducted in the area nor any progress made. When YUVA along with community leaders went to enquire about the survey, administrative delays were cited as a reason.

Image 3: Campaign carried out by All Guwahati Slum Coordination Committee

And till January 2021 survey had still not taken place when once again residents went to enquire post the second wave of COVID19, the electricity department now quotes another reason for the delay i.e, the location of the community makes it difficult to get electricity connection, even though both the settlements around Babu Basti, located in the same direction in front of and behind Babu Basti are electrified. When the residents agreed to bear the additional costs of setting up, the SHO informed them that they would require a No Objection Certificate/ NOC from the Railways as the settlement is situated around the railway line.

When the community leaders along with YUVA approached the railway department for a NOC, they were informed that there is no need for issuing such NOC if the Electricity Department wants to electrify the settlement, they can go ahead and do it. A Delhi and Kolkata High Court order said that all informal settlements are entitled to electricity. But these bureaucratic delays have meant that people are not being able to access their basic entitlements.

Here is a testimony from the ground which bring out the challenges of living a life without electricity in this day and age:

Riya (Name changed to protect identity)

Riya is a class 11 student who stays with her sister and parents in Babu Basti. Her sister is a class 5 student in a government school near their locality. Riya’s mother is a domestic worker and her father works for pandal decorations. The family, tired of waiting for the state electricity department to do something, invested in a portable solar energy plate. But during summers with the littler energy it conserves, they can use fan and light only during one half of the day either during the morning or at night. In addition to that, during the Assam monsoons, they are unable to use even this resource because of cloudy skies.

Post sunset, Riya and her sister study using candles especially during exams when they have to spend longer hours. The trouble is not just in studying but also in accessing toilets at night. In a particular incident Priya when she went to use the washroom next to her kaccha house, she found a snake lurking in the dark. They also frequently face the fear of evictions and floods that disrupt their lives. With these challenges families like Riya’s are denied their dignity and there is an urgent need to facilitate access to basic services and entitlements that are their right.

After higher secondary education, Riya wants to pursue a bachelors degree in commerce from Guwahati Commerce College for which she needs to secure high marks in her exams. This becomes even more challenging in the absence of electricity.

Life without electricity in an urban informal settlement brings along many troubles for already impoverished households. In Guwahati where floods are recurrent and hardships for the underserved communities are many, lack of a service as basic as electricity prevents them from accessing many other services as well. For children and young adults in schools and college, studying post-sunset is not even a possibility or an option. Whatever studies that they manage to do post-sunset is done with candles and lanterns. What is important to remember here is that if children and adolescents are to access their right to education, they need conducive environments for studying. Therefore, the inaccessibility of electricity in Babu Basti has been forwarded for legal solution as the department was unwilling to take the matter into consideration. There are several cases of other metro cities where favorable judgments were passed regarding access to electricity, and therefore we are also hopeful of receiving a positive response from the court.

Note 1: Census of India-2011 has categorized slums into following categories: a) Notified Slums, b) Recognized Slums, and c) Identified Slums. All areas in a town or city which have been notified as ‘Slum’ are classified as Notified Slum. All areas recognized as ‘Slum’ but may not have been formally notified as slums under any statute, are classified as Recognized Slum. A congested area of a population of at least 300 persons or about 60-70 households with poorly built congested sites, in an unhygienic environment usually with inadequate infrastructure and a lack of proper sanitation and drinking is categorized as an identified slum.

Note 2: In Situ Slum Redevelopment (ISSR) is a component of PMAY where central assistance of Rs. 1 lakh per house is provided for all houses built for eligible slum dwellers using land as Resource with participation of private developers.

Syeda Mehzebin Rahman is the Project Lead in Guwahati for Youth For Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA).