The power of youth is the common wealth for the entire world. The faces of young people are the faces of our past, our present and our future — Kailash Satyarthi

India’s youth are a precious asset. They signify potential, energy and zeal for social good, and their development should be the nation’s priority.

The National Youth Policy 2014 under India’s Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports is the overarching policy to address the varied needs of the country’s youth. It was recently reviewed and launched as a new draft National Youth Policy, with a 10-year vision on different aspects of youth development. The Ministry sought suggestions on the policy draft from all stakeholders till 15 July 2022.

The policy promises to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and seeks to ‘unlock the potential of the youth to advance India’. It focuses on five priority areas, education; employment and entrepreneurship; youth leadership and development; health, fitness and sports; and social justice. The policy states that each priority area will be ‘underpinned by the principle of social inclusion’ to adequately support underprivileged communities, but it fails to specify the modalities of how it plans to achieve these goals.

For any policy to be a success, people impacted by it should be at the forefront of the policy making process. People’s participation ensures that the policy is responsive to their needs, and schemes designed reflect the needs of the community to ensure equitable and sustainable development.

The policy is very straight cut, we don’t see how the execution will happen and how it will suit the needs of the people belonging to both rural and urban areas.- Pranaya Patade, Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) District Secretary, Anubhav Shiksha Kendra

Even a quick analysis of the draft National Youth Policy reveals its disconnect from ground realities. The document mentions mechanisms, like grievance redressal for youth, without detailing how they will work or who will be responsible for implementing them.

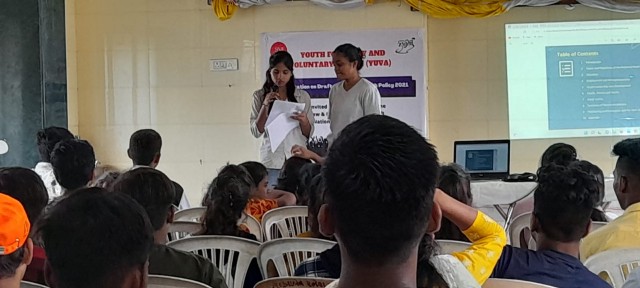

To help youth across Maharashtra better understand and respond to the gaps in the National Youth Policy, YUVA hosted 27 consultations across 19 districts across June–July 2022. Through a participatory process, the consultations engaged 1,983 youth to spread awareness about the policy and encouraged them to critically analyse it and articulate gaps in the policy. These suggestions have been submitted to the Ministry.

Let’s learn a little more about the participatory approach, the bedrock of this process, and how it helped the youth articulate policy gaps and needs.

The role of a participatory approach to strengthen policy making

Participatory approach refers to the active association and involvement of the people or community in policy formulation, project planning or implementation. It is based on the belief that people have a right to participate in the institutions and decisions that affect their lives. Under the participatory approach, the integration of social, cultural and economic factors is taken into consideration. Like Shahenshah Ansari, youth leader, Mumbai Western Suburbs, explains, ‘only I know my circumstances, and only I know what support I need from the government. But if I don’t have the proper resources or the mechanisms my development will stop’. How is such a policy different from the others that exist in our country? How is it promising sustainable growth? ‘As we say, India has a dense population of young people, but if the policies being made are not from our perspective then their implementation will be unsatisfactory’, he says.

Shahenshah also talks about the interconnection between his surroundings and his growth. He says, ‘my development is interlinked with everything, be it education or health, and for my growth I will need the support of everyone, my family and the government’. Participatory approach allows the interlinkages a space to form a coherence, with the ‘leave no one behind’ principle and ensures holistic and sustainable development.

The approach places emphasis on the role of diverse stakeholders for lasting and positive change. Government officials play a crucial role as they drive the implementation of such policies. But as Asma Ansari, MMR youth leader, explains ‘the stakeholders themselves don’t know what they have to provide and to whom. They are not sensitised towards our needs, so how do we expect them to provide us services like counselling’. To ensure gaps like these are minimised, a capacity building model needs to be developed to increase stakeholders awareness’ and sensitisation on the issues of youth and how to address them.

The participatory approach in the development process not only brings people together but also encourages ownership among communities and pushes for people’s participation in decision making. As Shahenshah explains through an example, ‘if there is land, the government will develop it according to what they feel will benefit the community, but they don’t know how that will affect us. But if the same land is used after consulting the people of the community, then they will come together and use it in a way that will actually benefit them. That coming together will not only ensure sustainability but also empower them to make decisions based on their needs’.

Critically appraising the National Youth Policy through the participatory approach

Furthering this participatory approach for change, Citizen Matters and YUVA recently hosted a discussion among youth leaders from across the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), to understand their analysis of the gaps in the National Youth Policy. Due to the expansive youth development and support areas, not all issues could be covered. A few highlights of the discussion are detailed below.

Reflecting on the participatory approach, Pranaya said, ‘I feel our participation is important, because these are our issues. Somebody from outside cannot come and tell us what is good for us, no matter how good their intentions are’’. She believes that representation in such policies is very important. ‘I don’t see anybody representing us in the governing bodies, there is no youth involvement while making policy decisions’. Pranaya’s participation in YUVA’s City Caravan inclusive cities building programme, recently took her to Brazil and she shared the scope for youth expression she witnessed there. ‘I saw that the youth there had a space in their assembly to discuss youth affairs. They represented their problems in such forums and helped in forming better policies, but we don’t have this in our country, where our population is in the majority’.

Adding to this, Swapnil, MMR District Executive, Anubhav Shiksha Kenda, shared, ‘The policy does not clearly outline how implementation will take place. For instance it talks about quick justice, but how will that be delivered? We will need fast track courts for that’.

Sana Shaikh, youth leader, Mumbai Eastern Suburbs, shared how she feels inclusion is very core to a policy. She spoke about the lack of inclusion of people from other genders, saying, ‘they have talked about creating mechanisms for marginalised sections, LGBTQI+ community, girls and young women, but nothing is in detail. We don’t exactly know how inclusive these mechanisms are because we don’t know what they are’.

The youth also discussed their personal journeys and experiences when it comes to the National Youth Policy and how it affects them. They spoke about education, finance, mental health, leadership and development. Pranaya shared insights regarding teachers and how their training and sensitisation can support youth needs. ‘So many times we hear that teachers hit children, but we never take it seriously because it is so common. No one talks about the effects of it on a child’s mental health’. She shared that there is a lot of discussion about mental health in the National Youth Policy, but how the policy ensures its implementation is not clear.

The key areas the youth touched upon in their discussion included the need to build awareness among youth regarding this policy, looking at education in a more holistic way (from higher education needs, affordable course fees, career counselling, to considering the multiple reasons for dropouts and addressing this sensitively), stronger explanation of what implementation will be in all cases, and more.

Catch up on the complete discussion here.

Kisa Kazmi, reviewed by Doel Jaikishen